- Get Started For Free →

Our Best Lives Were Never Meant to Be Lived Alone

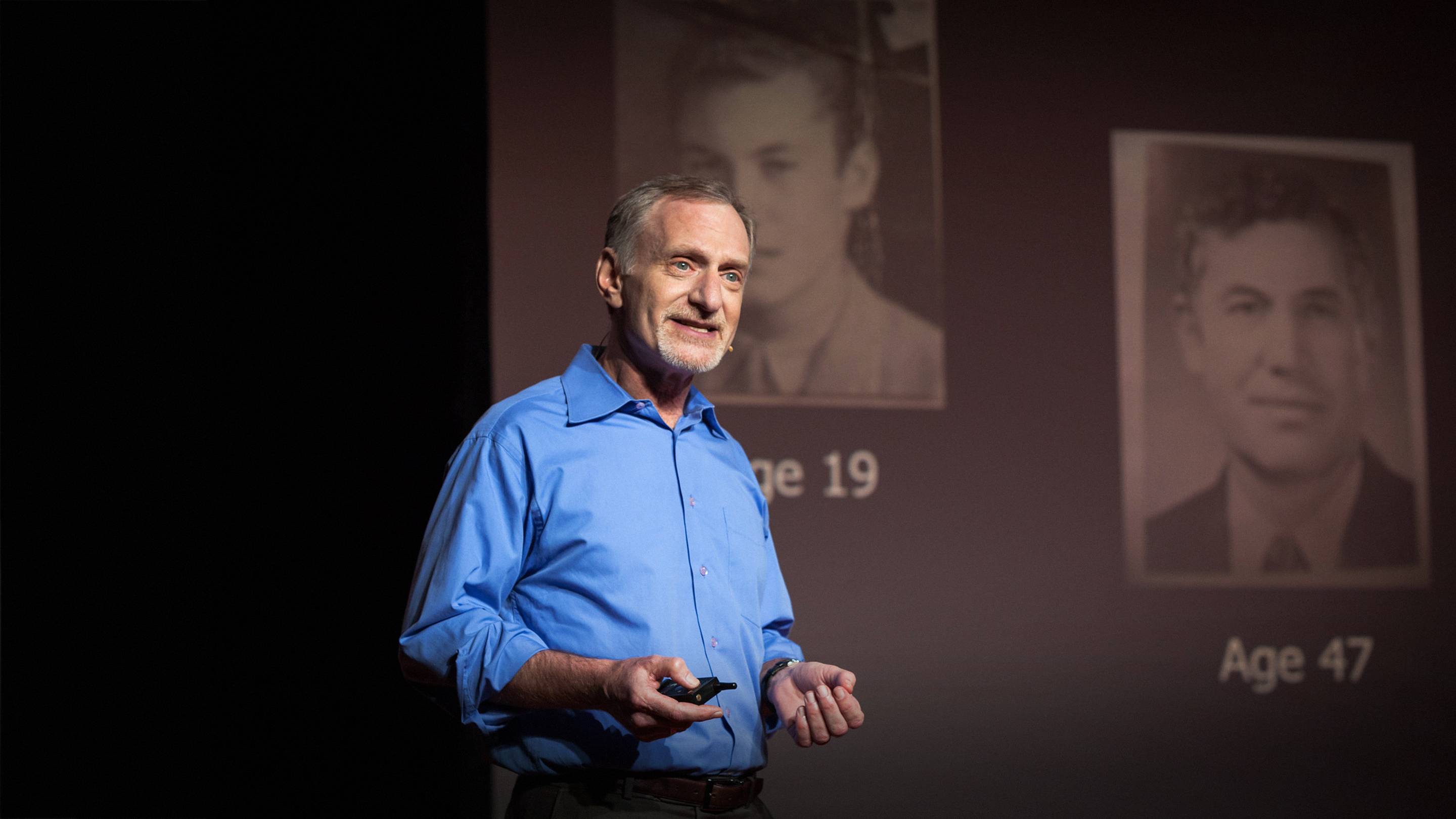

Robert Waldinger at his 2015 TED Talk 'What makes a good life? Lessons from the longest study on happiness.' (Source: TED)

Harvard researchers found fulfilling relationships have a positive impact on our health and wellbeing.

“What if we could watch entire lives as they unfold through time…to see what keeps them happy and healthy?” asks Massachusetts General Hospital psychiatrist Robert Waldinger in a 2015 TED Talk.

Happiness is the age-old problem nearly every culture has tried to solve: The Greeks pursued Eudaimonia, or full-human flourishing, through the practice of set, rigorous principles. The Romans built extensive public hygiene systems for physical health and wellness at a societal level. The rise of Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, and other religions attempted to grow emotional and spiritual health. Across the world, public health and welfare campaigns, pioneered by religious institutions, scientific advances, and more, have made ongoing attempts to drive humanity closer to health and happiness. But seemingly no one has tracked a person's self-reported well-being over time.

“Well,” Waldinger continues in his TED Talk, “we did that.”

The Harvard Study of Adult Development

In 1937, Harvard researchers, determined to understand what cultivates and sustains long-term health and happiness, undertook a study projected to literally last a lifetime. Or several.

Two cohorts were chosen: The first, referred to as the Grant study, consisted of 268 Harvard men around 19 years old. Although a far from varied sample size, this data set unintentionally allowed researchers to look at holistic fulfillment beyond basic needs, the experience of a privileged population with adequate sustenance, shelter, and security. The second, selected by Harvard Law School professors Sheldon and Eleanor Glueck, contained 456 males ages 11 to 16 from neighborhoods throughout Boston, aiming to address the Grant study's lack of diversity in participants. Eventually, the study grew to include spouses and children, transforming into the Harvard Study of Adult Development.

Every two years, Harvard researchers checked in with these groups, asking them about their habits, routines, and lives. But instead of providing a survey to complete and entering in data sans context, these researchers opted for conversations and genuine connection with participants. Coincidentally, this would become the most significant aspect of both the cohorts’ responses and the researchers’ methodology.

Developing Connections is Our Default

The consistency and longevity of the study itself is a testament to not only human nature’s drive to find happiness but also our tenacity in maintaining human connection.

“To get the clearest pictures of these lives, we don’t just send them questionnaires,” says the aforementioned Robert Waldinger, fourth director of the Harvard Study of Adult Development. “We interview them in their living rooms, we get their medical records from their doctors, we draw their blood, we scan their brains, we talk to their children, we videotape them talking with their wives about their deepest concerns.”

Simply put, the narrative arc of these people mattered to the researchers; they wanted to follow the trajectory of these lives as much as they wanted to pass on the study to the newest group of researchers interested in exploring the inquiry. Creating community and developing connections is our natural default—even when we don lab coats to study ourselves. The human factor cannot be ignored. And denial of this essential aspect of our lives has repercussions.

Our Relationships Affect Our Health

After following 742 men over 75 years and, subsequently, their spouses and children, the Harvard Study of Adult Development found the biggest factor influencing a person’s well-being was other people or rather, their relationships with other people.

“The surprising finding is that our relationships—and how happy we are in our relationships—has a powerful influence on our health,” explains Waldinger. “Taking care of your body is important, but tending to your relationships is a form of self-care, too. That, I think, is the revelation.”

If meaningful, fulfilling relationships have a positive impact on a person’s physical health and wellbeing, by extension, the opposite holds true. An absence of relationships beyond surface-level interactions causes measurable psychological and physical damage.

“Loneliness kills,” states Waldinger. “It turns out that people who are more socially connected—to family, to friends, to community—are happier, they’re physically healthier, and they live longer.”

An Epidemic of Loneliness

In US Surgeon General Vivek Murthy’s viral 2017 Harvard Business Review essay, he writes “we live in the most technologically connected age in the history of civilization, yet rates of loneliness have doubled since the 1980s.”

If human beings are now more connected than ever, able to communicate across the globe at all hours, it logically follows loneliness should wan. And yet. The culprit, then, must be how we use this technology to communicate, and with whom we choose to communicate.

In his article for The Atlantic titled “Why the Past 10 Years of American Life Have Been Uniquely Stupid,” Jonathan Haidt writes, “Social scientists have identified at least three major forces that collectively bind together successful democracies: social capital (extensive social networks with high levels of trust), strong institutions, and shared stories. Social media has weakened all three.”

Haidt likens this to the biblical story about the tower of Babel, citing the creation and rise of late-aughts social media platforms as the construction of the tower and the subsequent destruction of genuine human connection as the fallout from tech giants’ hubris, or pride. Straying away from theological associations, the advent of Facebook and other forms of social media have had a profound effect on how we react to one another—because reaction has replaced interaction. We have myriad online relationships, but we don't have the tools to stay in proper touch with the people who matter, the people with whom we want to grow closer.

“It's not just the number of friends you have, and it's not whether or not you're in a committed relationship,” as Waldinger reminds us, “but it's the quality of your close relationships that matters … and living in the midst of good, warm relationships is protective.”

As this brave new world of technological advancement unfurls around us, we need to make sure our lives unfurl with the support of good, warm relationships—our health and happiness depends on it. As pivotal as our relationships are, the current technology created to serve them only provides surface-level interactions. But technology itself isn’t the culprit here; it’s the intentionality behind the design.

That’s why we set out to design a digital tool for staying in touch with the people who matter to you—the people who make your life meaningful—sans saturated social feeds. This tool would honor the nature of your relationships through beautiful simplicity and intuitive design. We wanted to create a place you'd be happy to store your relationships. And so we created Clay.